Voci di scrittori contro Roma

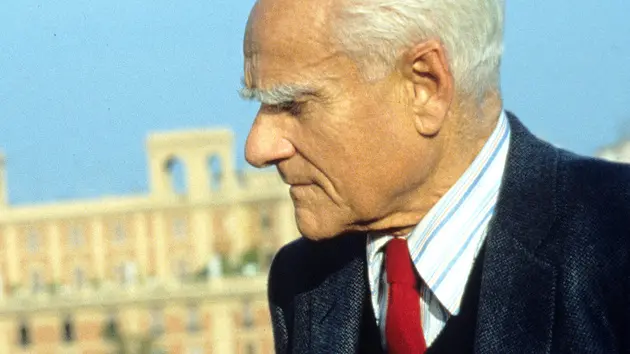

Il citatissimo Ennio Flaiano diceva «si viene a Roma in cerca di un lavoro poi si trova un impiego». Raffaele La Capria spiegava la differenza: «Un impiego è diverso da un lavoro, è qualcosa di molto più sottile e inqualificabile. Roma è prevalentemente una città di impiegati che non hanno trovato un lavoro e che lo stato mantiene in cambio di prestazioni incontrollabili». A che cosa serve questo esercito di impiegati? Secondo Alberto Moravia «Roma è diventata un elemento frenante e mortificante per la cultura italiana. A Roma non c’è una società borghese. La burocrazia non è una società. La provincia arriva a Roma con i suoi modelli culturali arretrati e anacronistici e rimane inassimilabile come un cibo pesante che resta sullo stomaco». E il sulfureo Eugenio Montale aggiungeva: «Produzione culturale? Nessuna. Oggi Roma ha molti scrittori, forse ne ha più che in ogni altra città, ma tranne due o tre non sono gran che. Credo abbia molti editori, e anche quelli non sono grandi editori. C’è però la possibilità di andare a Roma e di starci piacevolmente: questo si può ammettere. Ma in sostanza se uno può starne fuori non perde nulla».

Nel 1974 Bompiani aveva chiesto ad alcuni tra i maggiori scrittori italiani di dire le loro impressioni, si badi, solo negative, su Roma. Quarant’anni dopo Laterza aggiorna quell’operazione chiamando a raccolta una pattuglia di scrittori di oggi e riproponendo anche le pagine di quarant’anni fa. Esce così un nuovo ‘Contro Roma’ (pagg. 206, 16 euro).

Premesso che il confronto tra gli ‘opinionisti’ di ieri e di oggi è impari, la ‘formazione’ del 1974 vince a mani basse su quella del 2018, e che spiccano alcune assenze come Pasolini, che pure Roma ha amato e descritto nei libri e nei film, e Arbasino - cosa avrebbe detto lo snob lombardo di una Roma che aveva percorso in spider nei Sixties all’italiana? – dal confronto tra questi due sguardi collettivi emerge come sia cambiato il dibattito su Roma. Quarant’anni fa le si imputava di non essere adeguata al ruolo di capitale, Guido Piovene ricordava che «per D’Azeglio il trasferimento della capitale a Roma fu una sciagura nazionale, Manzoni non ebbe voglia di andarci, Cavour nemmeno, Vittorio Emanuele II scese solo per obbligo e non ne vide quasi nulla».

Ora invece, dopo le giunte Veltroni, Rutelli, Alemanno, Raggi siamo arrivati alle buche, agli autobus che bruciano, al rumore: «il silenzio appare come le praterie del selvaggio West, una terra di conquista, un bottino da spartire» scrive Valerio Magrelli. La capitale ha abdicato al suo ruolo, rimane il sempiterno cinismo. «A Roma - aggiunge Nicola Lagioia - non c’è nulla che valga la pena di essere mai davvero fatto. Ti smontano ogni cosa. Che stai a fa’? Stai a scrive un romanzo? Stai a fa’ un film? Stai a fa’ un giornale, ‘na rivista? Ma chittesencula?».

Anche la nostalgia è un’arma spuntata, il romano se ne beffa. Paolo di Paolo pensa a Fellini, al suo film su Roma, col regista che insegue Anna Magnani e la blandisce come fosse la città «aristocratica e stracciona, lupa e vestale, terrea e buffonesca». E la Magnani: «Federì, va a dormì».

In un divertente rap Christian Raimo solleva il problema della casa. «Va elemosinata una stanza a casa dei nonni scommettendo su una morte da infarto per potersi permettere un morbido ritorno da Erasmus». Ma infine, tutto andrà sempre peggio o ci sarà una redenzione? Un’altra Roma è possibile, ha fiducia Antonio Pascale, «tuttavia anziché dichiararlo con grida, disprezzo, odio è meglio dimostrarlo».

©RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA

Riproduzione riservata © Il Piccolo